The Challenge

Project Real, a non-profit organization aligned with UN Sustainable Development Goal 4 (Quality Education), challenged us to explore how we could empower young people to combat the spread of online misinformation.

Research Approach

To understand the misinformation crisis facing young people, we conducted:

Desktop research analyzing academic papers, news articles, and documentaries on media literacy

Primary interviews with 30+ participants across multiple age groups: children (10-13), teenagers (14-19), young adults (20-30), parents, teachers, and content creators

Stakeholder workshops with Project Real to understand organizational goals and constraints

What We Learned

The Crisis is Real

Online misinformation spreads 6 times faster than truth, and only 4% of people can systematically distinguish fact from fiction.

Nearly half of young people aged 11-16 believe news they see on social media, with 84% of youths admitting they're unsure how to verify what's real.

Age 13 is when children start believing conspiracy theories—making 11-13 a critical intervention window.

Young People Are Overwhelmed

When we spoke to 11-year-olds, the responses were telling. One admitted, "I don't know what real is anymore because we depend so much on social media." Another had never heard the word "misinformation" or "deepfake."

A 15-year-old showed more developed critical thinking: "I wouldn't say I believed something and found out it was untrue, but I've seen something and it's caused me to research it more." Yet even older teens acknowledged: "Friends believe stupid things; they trust the internet more because they haven't been taught not to."

Traditional Approaches Won't Work

Educators told us: "This generation does not watch TV. They watch YouTube, which is always based on someone's opinion. They like influencers, they like games—it's not teacher talk, it's videos and discussions."

Parents revealed their own struggles: "We're too busy and unaware, so we just give kids phones or iPads to entertain them." Teachers noted: "My pupils are constantly on their phones - not reading as much."

The consensus: lecturing kids about misinformation won't work. They need something different.

The Opportunity

Through our research with Project Real, we discovered something powerful: kids are motivated by feeling clever. When they spot fake content, they feel superior—"I found it and no one else did." This positive emotional reward could become "an engine unto themselves to become the influencers they admire."

Young people also told us their motivation for calling out misinformation was clear: protecting their friends. Framing media literacy as "keeping your friends safe" resonated far more than "don't believe everything you read."

The Insight

Young people aged 11-13 are at a critical crossroads. They're old enough to engage with complex ideas but young enough that their media literacy habits haven't solidified.

Traditional education that lectures will fail. But empowering them to become heroes who can spot misinformation—making them feel clever when they outsmart fake news—could transform media literacy from a chore into a superpower they actually want to develop.

Synthesizing the Research

After conducting extensive research with 30+ participants across multiple age groups and analyzing the misinformation landscape, we needed to transform our insights into a clear problem definition and actionable design direction.

Who We're Designing For

We identified three key user groups, each with distinct needs:

Primary Users: Young People (11-13)

This age group sits at a pivotal moment—old enough to understand complex concepts but young enough that their information-consumption habits are still forming.

Our research revealed they feel overwhelmed by information but don't know how to evaluate it, are motivated by feeling clever and protecting their friends, and respond to games and challenges rather than lectures. They want to be the heroes, not the victims.

Core need: Empowerment through skill-building that feels rewarding, not remedial.

Secondary Users: Educators

Teachers and facilitators told us they have limited time and can't add complex prep work, need solutions that work across various settings (classrooms, clubs, camps), want ways to measure whether learning actually happened, and struggle to compete with phones and social media for attention.

Core need: "Pick-up-able" resources that engage students without extensive training or preparation.

Tertiary Users: Parents

Parents expressed frustration about being too busy to monitor everything their kids see online, not understanding the misinformation landscape themselves, wanting to be part of the solution but lacking the tools, and seeing their kids trust internet sources over family guidance.

Core need: Simple ways to reinforce media literacy at home and open conversations about online content.

Design Principles

From our research insights, we established five core principles to guide our solution:

Empowerment over Education - Make kids feel like heroes, not students

Fun over Fear - Use engagement and positive reward, not scare tactics

Peer Protection - Frame media literacy as protecting friends, not self-protection

Agency over Authority - Give kids tools to verify themselves rather than relying on adults

Simplicity over Complexity - Solutions must be immediately usable without extensive setup

Success Metrics

We defined what success would look like across our user groups:

For Young People: Voluntarily engage with the solution without being forced, demonstrate ability to identify misinformation tactics, report increased confidence in spotting fake content, and share what they learned with friends.

For Educators: Adopt the solution without requiring extensive training, report strong student engagement, and observe behavior change in how students discuss online content.

For Parents: Understand what their children are learning, report meaningful conversations at home about media literacy, and feel equipped to support their children's digital navigation.

The Design Challenge

11-13 year olds are at a critical developmental stage where media literacy habits form, yet they lack the tools and motivation to distinguish truth from misinformation. Traditional educational approaches fail because they lecture rather than empower, creating disengagement rather than building critical thinking skills.

How might we create an experience where 11-13 year olds discover they have the power to protect their friends by outsmarting misinformation—making critical thinking feel like a superpower they want to develop—while requiring zero teacher prep time and working across multiple environments?

Design Hypothesis

We believe that making young people feel good about spotting fake news through interactive community-based mediums will result in an expanded sense of responsibility, empathy, and critical thinking in real-world situations while fostering collaborative learning—because young people inherently feel smart and capable when they can identify and correct mistakes. They love engaging their imagination and are motivated by competition. These interactive experiences involving their community will foster discussion, diverse perspectives, and learning.

Ideate

Understanding the Landscape

We explored existing media literacy solutions—digital games like Bad News and The New York Times Simulator (Molleindustria's), Google's Prebunking website (which inspired our manipulation tactic cards), Rumour Guard, fact-checking plugins, and educational video series from Checkology and the News Literacy Project.

While these had merit, they shared critical limitations: they required technology access, felt like homework, and weren't ready to use out of the box for teachers who had zero prep time.

Co-Creating with Kids

Rather than assuming solutions, we asked kids directly: "If you had to create a tool to help someone your age spot fake news, what would it look like?"

Their answers were clear. Videos? "Meh, boring." Puzzles? "No." Educational app? "Maybe if it's on my phone." But games? "As long as it's not educational and it's fun," "A game teaching you would be fun," "With friends, maybe by myself if it's fun." They wanted something that felt like a break, not school—"Not being too serious, using slang."

Why the Card Game

We explored digital plugins, influencer video series, online scoring systems, and various game formats. The physical card game won because it uniquely satisfied every constraint:

For kids: Game first, education second. Social and competitive—tapping into their natural desire to win and be right, turning their ego into the engine that drives learning. Creates "I'm clever" moments without feeling like school.

For teachers: Zero tech, zero prep, works anywhere

For scale: Affordable, no platform dependencies, works with or without internet

We decided to create both a physical card game for immediate accessibility and tactile engagement, and a digital version for scalability and environmental sustainability—giving educators and families the flexibility to choose what worked best for them.

Most importantly, it aligned with our design principles—empowering not lecturing, fun not fear-based, positioning kids as heroes. The research had pointed us here all along.

Prototype

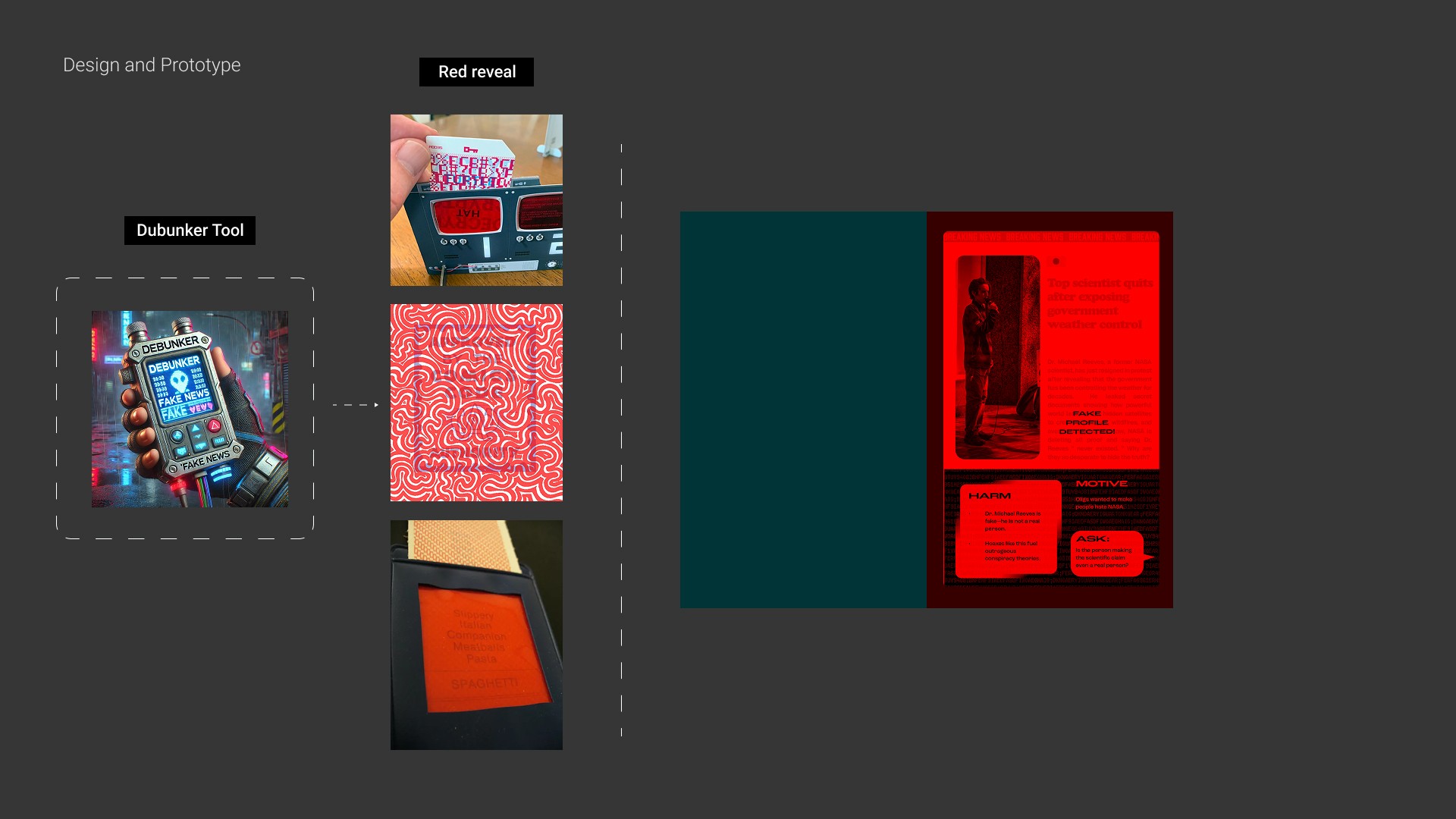

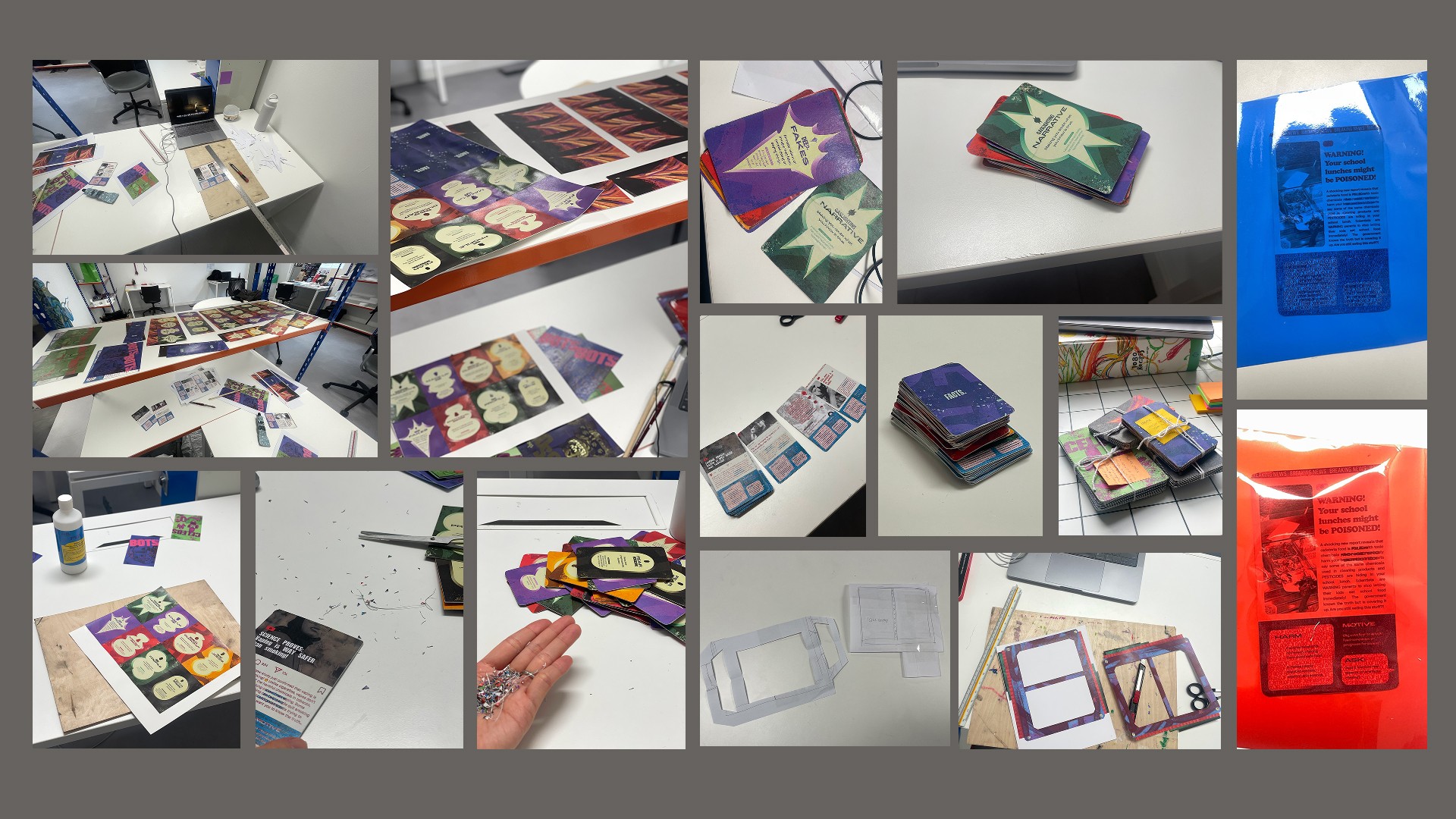

Building Two Versions in Parallel

We developed both physical and digital versions simultaneously to maximize accessibility and give users choice. The physical game prioritized tactile engagement and zero tech barriers, while the digital version offered scalability and environmental sustainability.

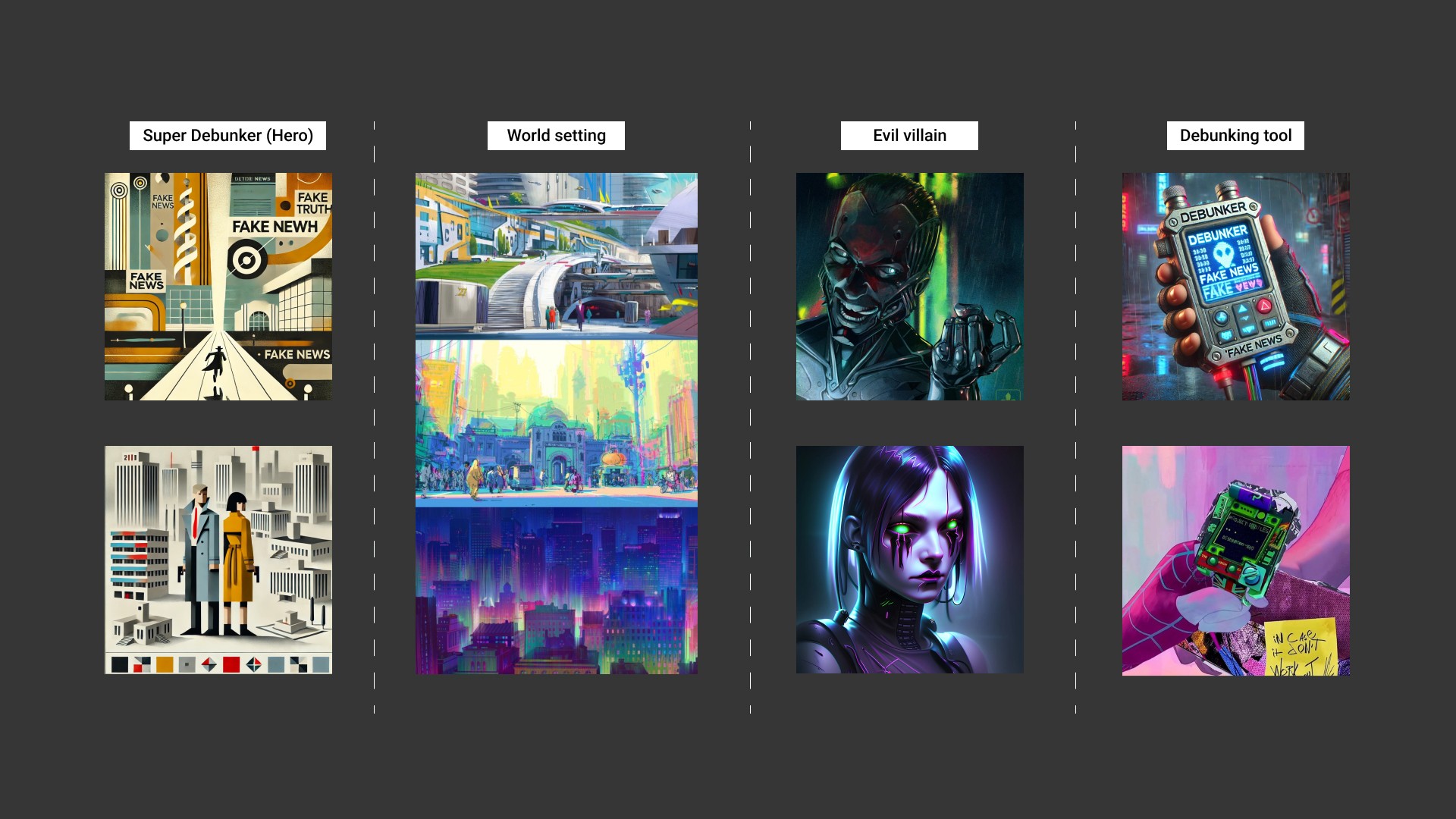

Narrative Framing

We framed players as Super Debunkers—heroes on a secret mission to protect their community by spotting misinformation before it spreads. Instead of traditional point scoring, players "save followers" from falling for fake news, turning their protective instinct into the game's reward system. This narrative directly addressed our research insight that kids are motivated by protecting friends and feeling clever, transforming media literacy from an academic exercise into an act of heroism.

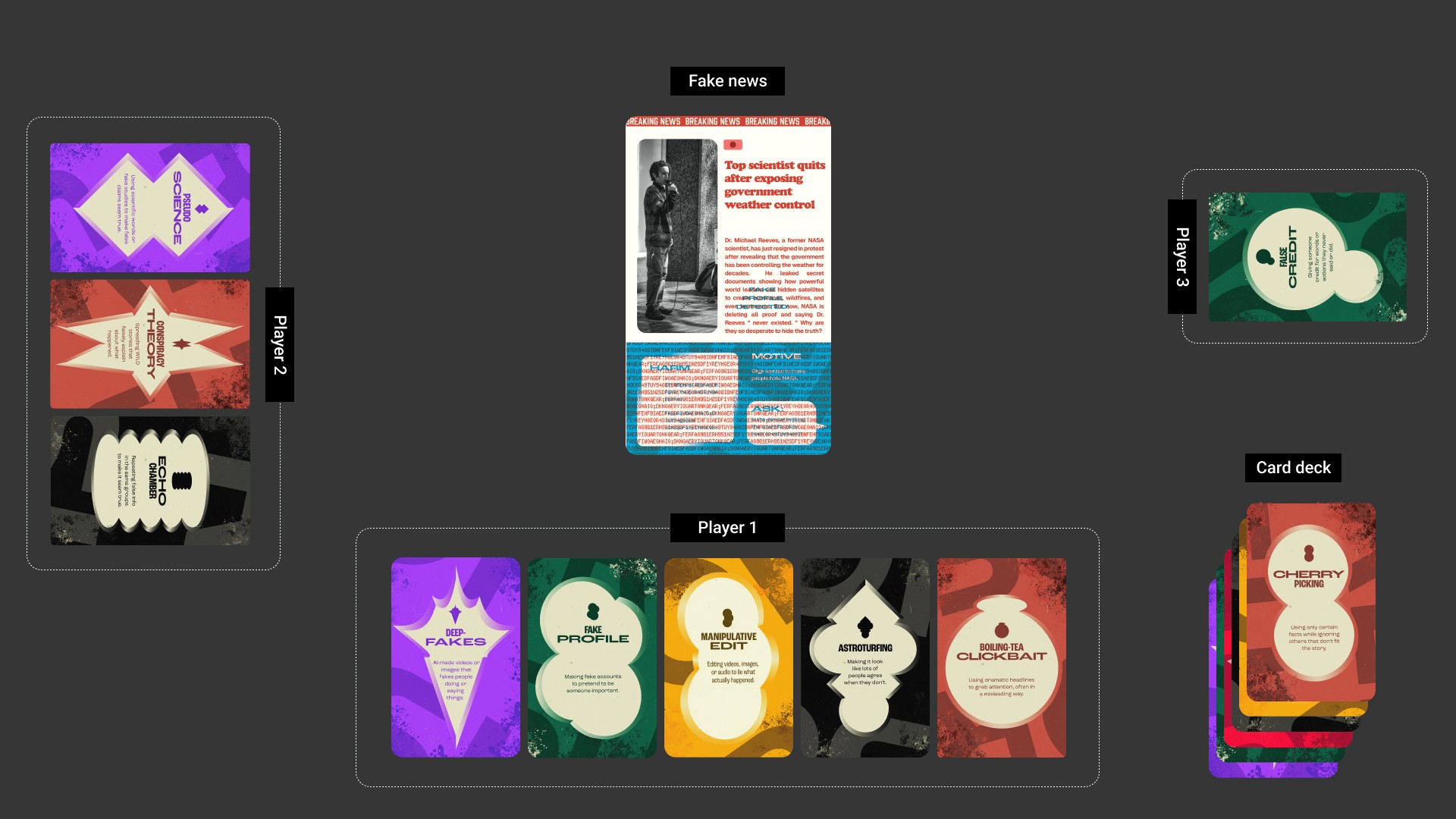

The Game Mechanics

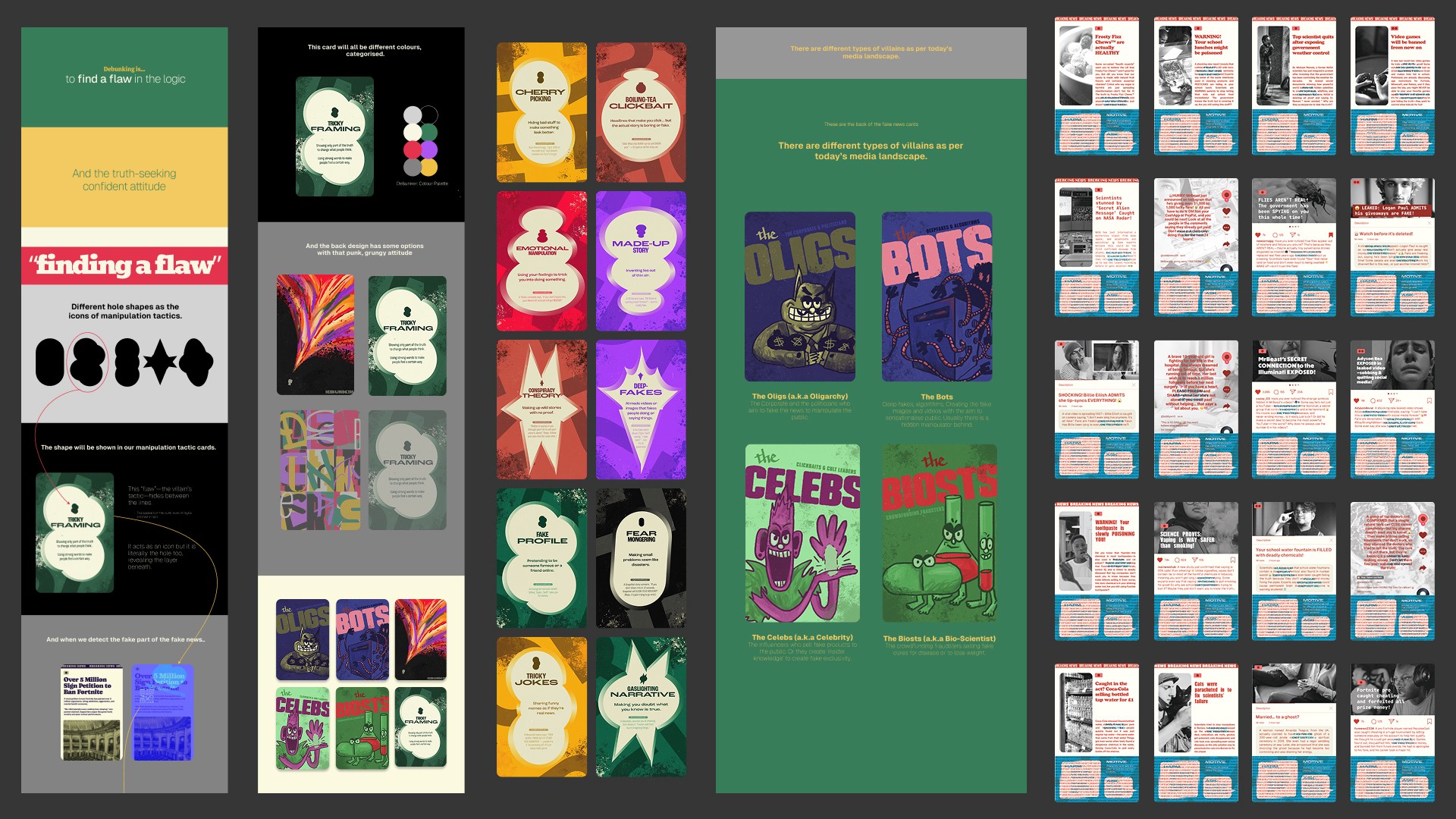

Super Debunkers transforms media literacy into a competitive mission where players become heroes protecting their community from four villains spreading misinformation:

The Oligs - Manipulate news for power and profit

The Bots - Spread sensationalized deepfakes and algorithm-driven lies

The Celebs - Fabricate exclusivity and promote fake products

The Celebs - Fabricate exclusivity and promote fake products

The Biosts - Scam the public with fraudulent cures

How it works:

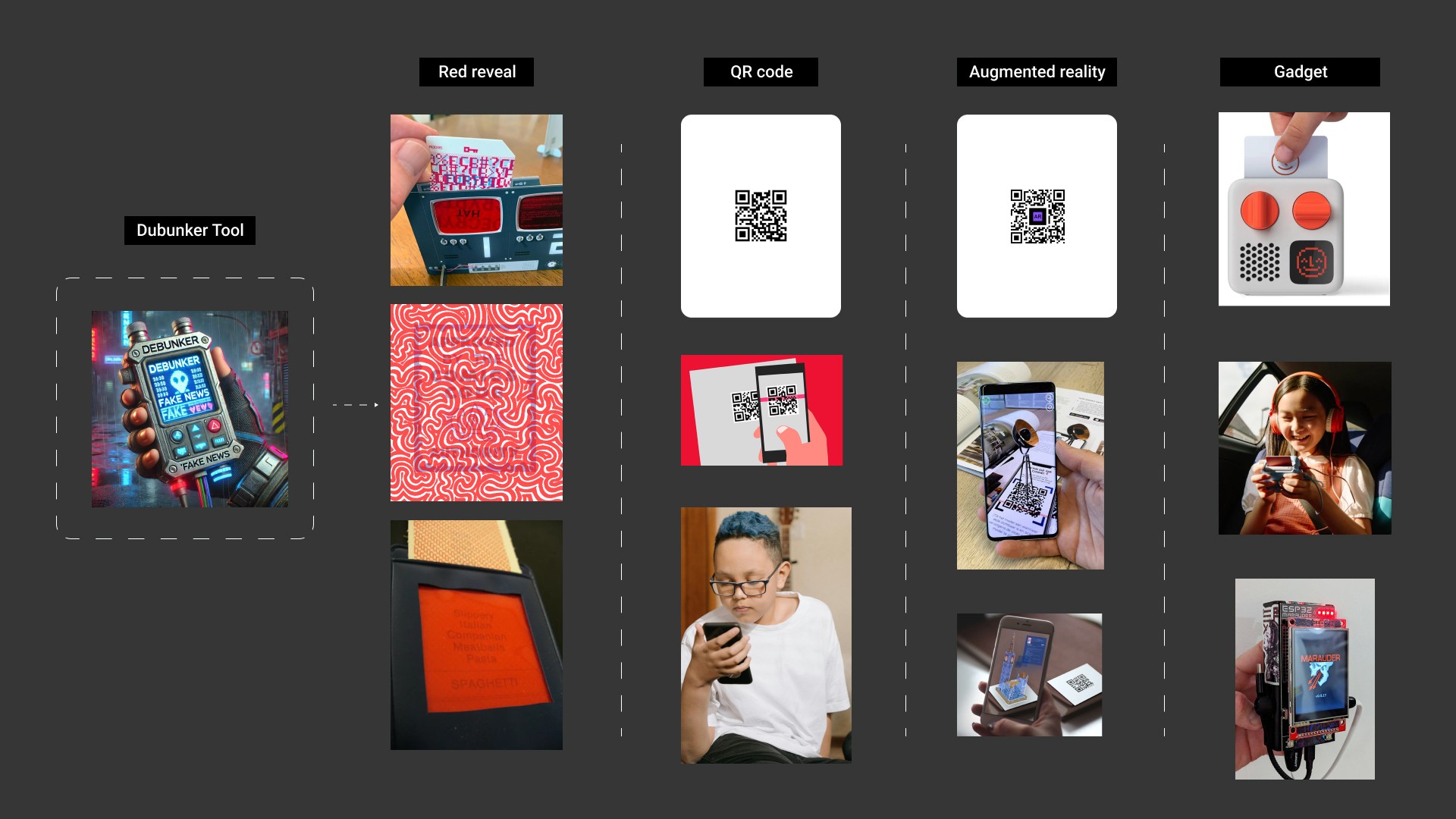

1) Players receive 10 Tactic Cards teaching manipulation techniques (inspired by Google's Prebunking)

2)Draw a News Card and place it under the Blue Debunker

Choose which Tactic Card matches the fake news strategy

3)Use the Red Debunker (decoder device) to reveal if correct

Score points: +100 for correct answers, -50 for wrong, +50 bonus for 3-answer streaks

4) Player who saves the most followers wins and becomes the Super Debunker

Design Decisions

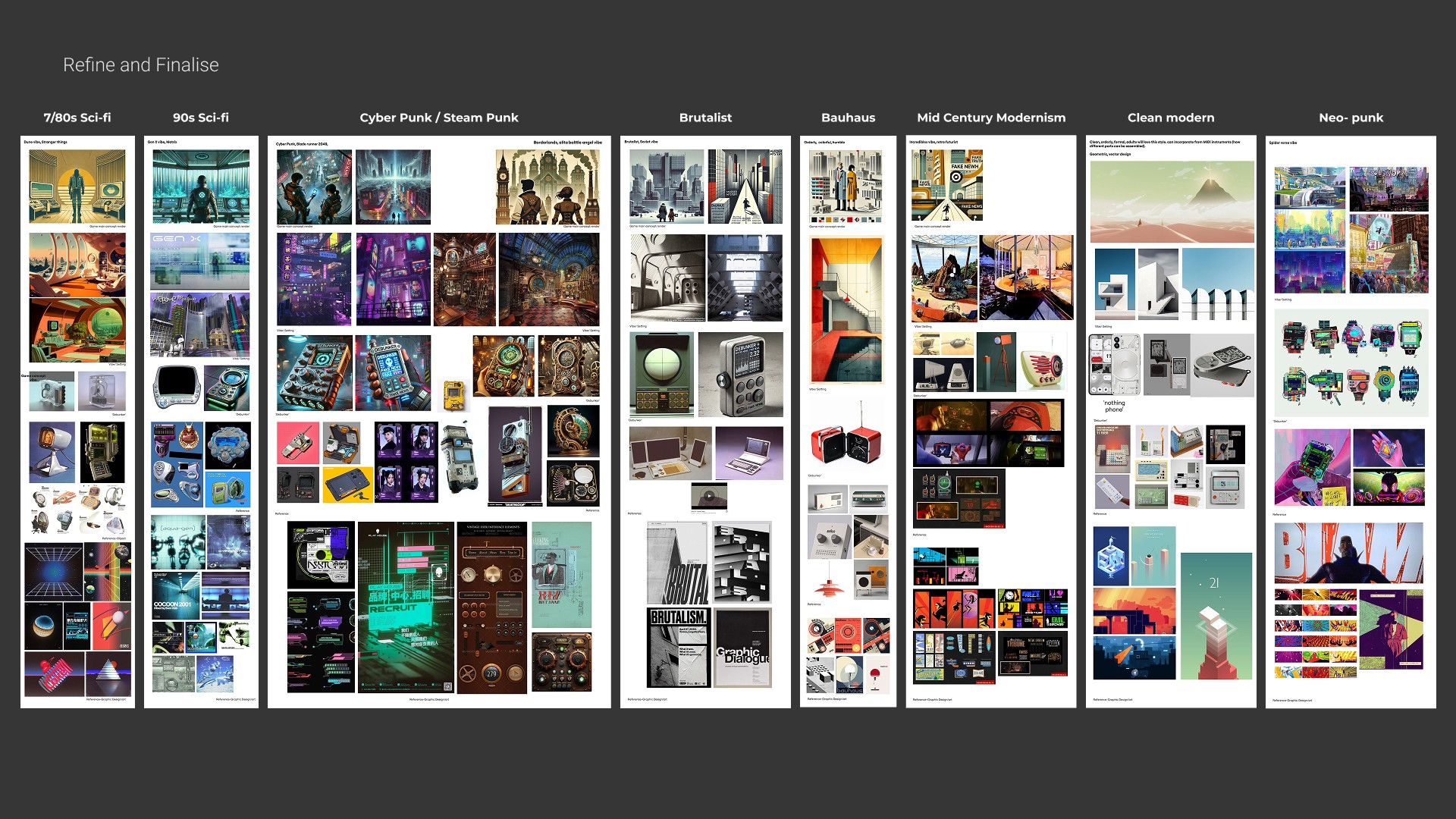

Visual Identity: We chose a bold graffiti/street art aesthetic with vibrant colors and villain characters that felt like a comic book or video game—not a classroom tool. This visual language resonated with our age group and reinforced the "rebellion against misinformation" theme from our punk philosophy framework.

The Red Reveal Technique: Inspired by spy decoder toys, we used red cellophane decoders that reveal hidden text on cards—creating a tangible "aha!" moment when players discover the correct answer. This tactile interaction made learning feel like uncovering secrets rather than studying.

Card Content: Each Tactic Card taught a specific manipulation technique with clear examples. News Cards contained both real and fake news relevant to 11-13 year olds' interests, avoiding controversial political topics while staying engaging.

Test

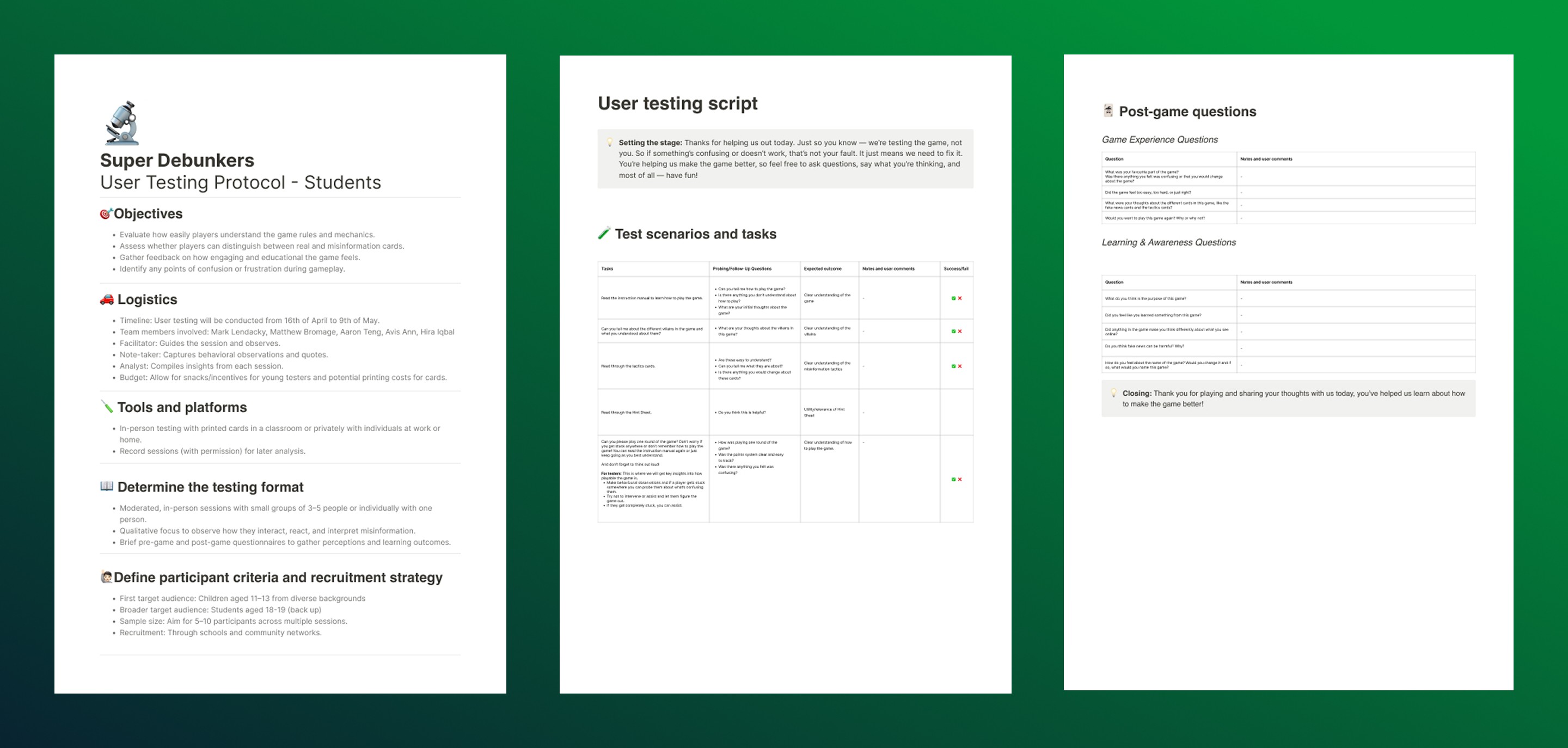

Testing Approach

We tested both physical and digital versions with 5 educators/education consultants, primary school teachers, and observed students playing the game in classroom settings.

What We Learned

Instructions: The language was engaging, but the instructions were too long—students were skipping ahead and struggling to retain focus. The most relevant gameplay information was buried on page three, and by the time users read it, they'd already started forgetting the earlier steps. Some classrooms found the game format unclear, particularly having one fake news card at a time with everyone guessing which tactics were used.

Villains: Most users (education consultants, teachers, students) didn't understand the purpose of the villains or their relationship to the fake news cards. The connection needed to be made more discoverable, potentially through color-coding fake news cards or making the graphics clearer on cards corresponding to respective villains.

Tactics: There was a lack of clarity in distinguishing between different tactics—some were too similar. The "Made-Up Story" tactic card was too broad, causing everyone to use it. We needed to reconsider the value proposition of the Conspiracy Theory and Made-Up Story cards. Additionally, it was difficult to figure out which tactics applied where, making the game frustrating when students kept losing. Educators suggested we might need to reconsider including Facts cards entirely, since distinguishing fake news from factual stories was challenging when both were sensationalized for gameplay purposes.

Digital UX: Some users struggled to understand how to move tactic cards to the right space in the online game. Generally, instructions for the online game were rated as easier to understand than the physical game, likely due to brevity and simplicity. Profile designs were fun but not visually distinct enough. Some testers were unable to get the online game going in classroom settings, even after reducing the number of players.

Overall Feedback: The game was praised as a fun and engaging way to teach students about different forms of misinformation. However, adjustments to the concept and execution would make it more straightforward and effective as a learning tool.

Key Iterations

Based on testing feedback, we made the following changes:

Content Changes:

Replaced "Made-Up Story" with "Sock-Puppetry" for clearer tactic distinction

Changed "Fake Persona" to "Sneaky Pretender" for age-appropriate language

Revised Conspiracy Theory and Made-Up Story cards based on educator feedback about nuance

Removed certain news cards that touched on topics DevOrg felt were inappropriate

Design Changes:

Reduced sentence length so we could increase font sizes across instructions and hint sheets

Made the two-card scoring symbol more obvious on cards (students were missing it)

Improved visual distinction for villain-to-tactic card relationships

Instruction Changes:

Shortened and simplified instructions significantly

Considered creating a teacher manual to walk students through gameplay rather than requiring them to read independently

Explored adding instructional videos for easier onboarding

Format Considerations:

Explored positioning the game as a whole-class activity rather than group-based

Considered laminated cards for physical version durability

Improved digital card interaction UX based on user struggles